The Capital Deployment Problem in Southeast Asia

Founders in Southeast Asia know the math of dilution, but the ecosystem’s incentives push them to behave as if the math doesn’t matter.

In our last piece, we made the case that most Southeast Asian businesses aren’t structurally suited for venture capital — based on market size, unit economics, and scalability constraints. What happens when you raise anyway? What does that do to your ownership, agency, and endgame as a founder?

Southeast Asian founders understand dilution. They can calculate ownership percentages, model cap tables, and predict what happens when you raise too much at inflated valuations. Yet the ecosystem continues to reward the same behavior: raise fast, burn hard, optimize for the next round rather than unit economics.

This isn't a knowledge problem. Founders aren't failing because they don't understand the math. They're failing because the system is designed to reward everyone except the people building the companies.

The Imported Playbook

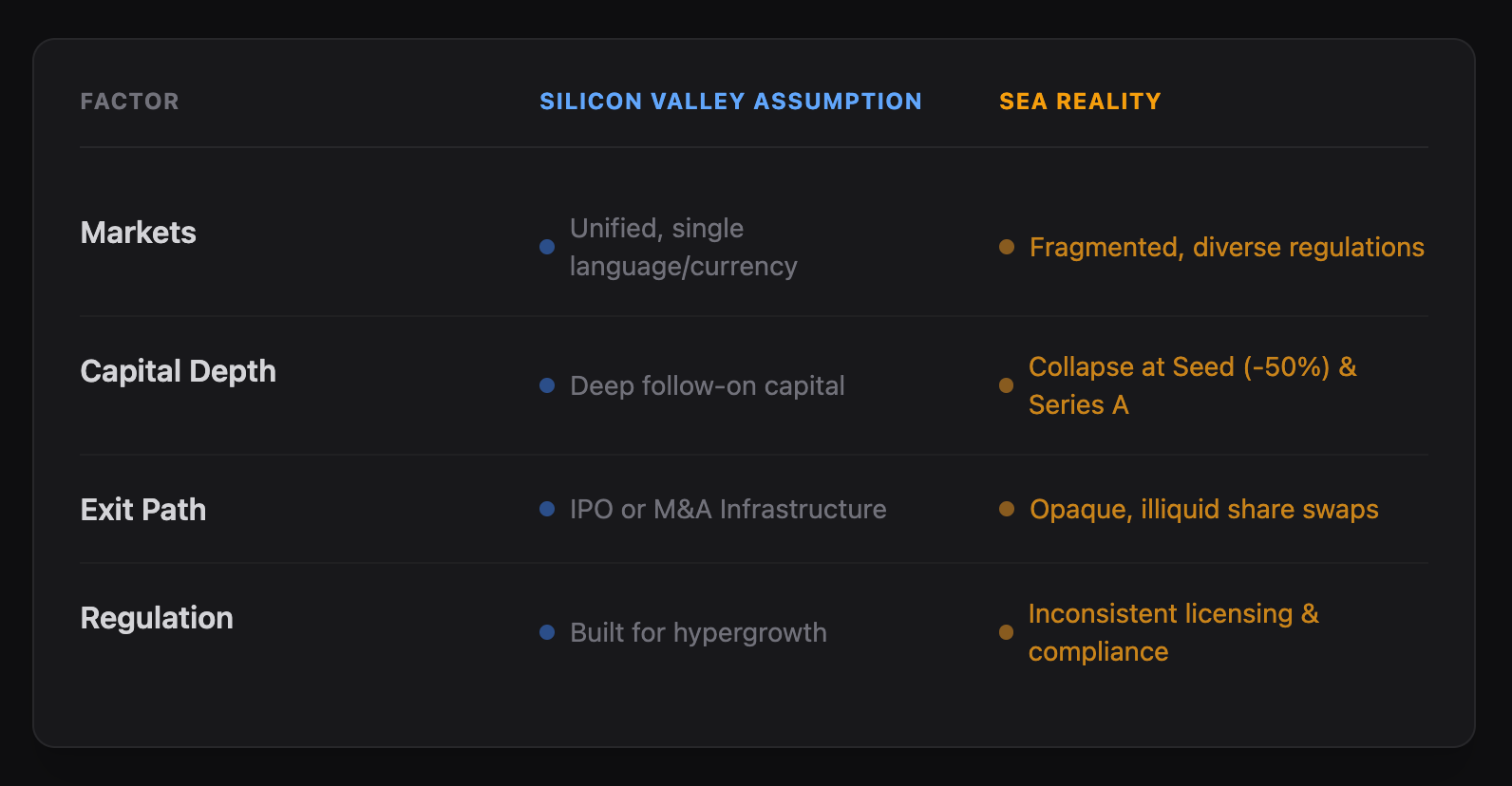

Southeast Asia's venture ecosystem was imported from Silicon Valley without adaptation. The model assumes unified markets, deep follow-on capital, reliable exit infrastructure, and regulatory environments built for hypergrowth.

None of these conditions exist in SEA. Markets fragment across languages, currencies, and regulatory regimes. Domestic markets are small enough that regional expansion is required just to reach modest scale. Follow-on capital collapsed 50% at seed and 27% at Series A in H1 2025. Exit pathways remain opaque, with only 28 exits recorded in the first nine months of 2024, most of them illiquid share swaps rather than real liquidity events.

Still, founders pattern-match to the Valley playbook. Not because it works, but because it's the only template the ecosystem recognizes. When 92% of SEA funding concentrates in Singapore, and that capital carries imported expectations, founders face a binary choice: conform to a broken model or exit the funding game entirely.

The Identity Trap

In Southeast Asia, founder legitimacy is constructed around capital raised. Fundraising announcements function as validation events that determine whether you're building a "real startup" or running a lifestyle business. The ecosystem treats funding rounds as proof of product-market fit, independent of actual traction.

If you bootstrap, you're invisible. If you grow slowly, you're irrelevant. If you don't raise, you're not serious.

Even founders who understand the dilution math fall into this trap because the alternative is professional invisibility. When employees, partners, and family members ask "How much did you raise?" as a proxy for "How well are you doing?", resistance requires cultural rebellion.

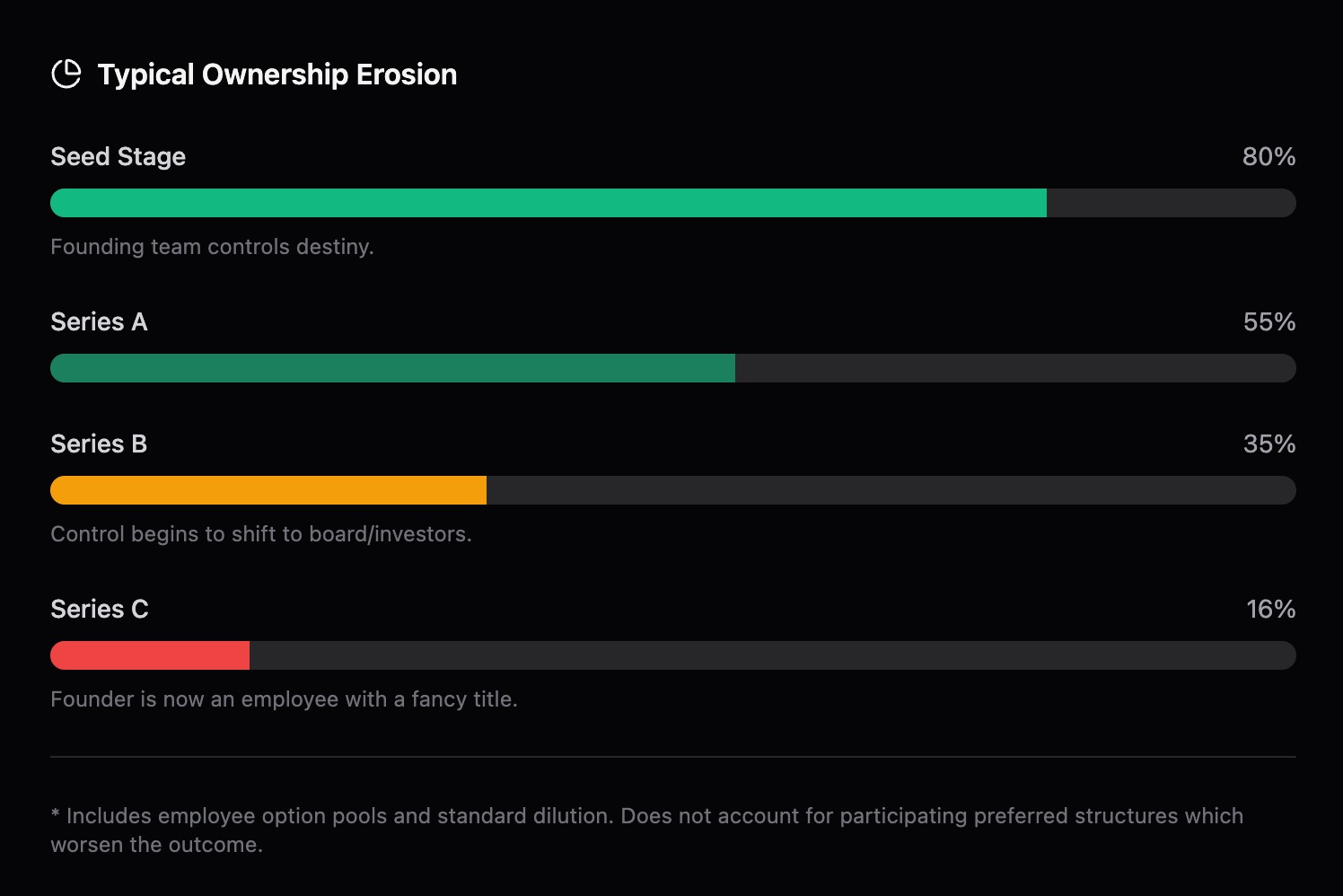

By the time a founder reaches Series C, they typically own 16% of their company. After an IPO or exit, that number often drops to 12% or below. With co-founders, individual ownership can fall to single digits. And because of liquidation preferences and participating preferred shares, founders are often last to get paid in an exit.

Who Benefits From Over-Raising

Most pressure to raise capital comes not from founders' needs but from everyone else's incentives.

Venture capital funds operate under deployment pressure. A $100 million fund generates $2 million annually in management fees regardless of performance. When GPs can earn $10-15 million per year from fees alone, the incentive shifts from maximizing carry (which requires successful exits) to maximizing AUM (which requires rapid deployment). Funds typically have 3-5 years to deploy capital, creating urgency unrelated to startup readiness.

Media platforms need content. Funding announcements are low-effort, high-engagement stories that fill editorial calendars.

Employees use funding as a heuristic for job security. Well-funded startups offer competitive salaries and stock options. The best talent gravitates toward companies that have raised, creating a self-reinforcing loop.

Corporate partners treat funding as a signal of seriousness. Large organizations filter for startups "validated" by institutional investors when evaluating partnerships or acquisitions, independent of actual traction.

Follow-on investors demand growth curves that only capital can buy. To raise a Series B, you need Series A-grade metrics. To achieve those metrics without burning cash requires years, but the fund lifecycle doesn't allow for patience. Founders over-capitalize in Series A to hit Series B metrics, then over-capitalize in Series B to hit Series C metrics, in an escalating game where the music eventually stops.

The Fear Economy

Southeast Asian founders over-raise out of fear, not greed. And that fear is rational given the structural fragility of regional markets.

Regulatory fragmentation means what works in Singapore doesn't work in Indonesia, and what's legal in Thailand might be prohibited in Vietnam. Founders navigate diverse receivables laws, inconsistent electronic documentation standards, and opaque licensing requirements. Compliance risks range from monetary penalties to operational shutdowns.

Market unpredictability amplifies when global markets contract. SEA feels it first and hardest. Funding dropped 85% from its 2021 peak, pushing 2025 performance to a six-year low. Founders who didn't raise aggressively when capital was available found themselves unable to raise at all when markets turned.

Governance risks loom large. The collapses of Zilingo and eFishery exposed how financial misconduct proliferates where private companies aren't required to file accounts, where cross-border subsidiaries escape oversight, and where auditing firms lack resources to catch fraud early.

Talent scarcity means losing a key engineer can set a startup back by quarters. Founders over-raise to create salary buffers that prevent defection to better-funded competitors.

Enterprise sales cycles in SEA take 12-18 months, requiring deep relationship-building. Founders need longer runways just to prove business model viability.

Raising becomes an emotional hedge in markets where time is not on the founder's side. The capital doesn't buy safety. It buys constraints.

What Gets Lost

Dilution is the visible symptom. The actual disease is loss of agency.

A founder who exits at $100 million with 8% ownership receives $8 million. But Series B investors with participating preferred and 1x liquidation preference take $15 million off the top. Series A investors take another $10 million. After legal fees and employee option exercises, the founder walks away with $5 million. Life-changing money, but not the outcome that justified seven years of 80-hour weeks and the opportunity cost of a senior corporate role.

The real loss is control. Over-diluted founders lose the ability to make strategic decisions without investor approval. When you own less than 20% and investors control the board, you're an employee with a fancy title.

Capital commitments create path dependencies. Once you've raised $20 million, you can't pivot to a slower, more profitable business model without violating investor expectations and risking a down round.

When you're burning $500,000 a month, you don't have the luxury of patient experimentation. Every decision filters through "Will this help us raise the next round?" rather than "Is this right for the business?"

Once you've accepted growth-at-all-costs capital, pivoting to profitability looks like failure rather than maturity. Investors who signed up for a rocket ship don't want a sustainable business.

When your cap table includes multiple layers of participating preferred shares and liquidation preferences, you've sold the company multiple times over. You can't accept a $50 million acquisition, even if it would be life-changing, because the preference stack means founders get nothing.

Better Questions

The ecosystem optimizes for the wrong metric. "How much did you raise?" measures capital accumulation rather than value creation, signaling rather than sustainability, momentum theater rather than competitive advantage.

How much optionality did you retain?

Founders with 60% ownership and $2 million in ARR have more paths forward than founders with 15% ownership and $20 million in ARR.

The first founder can sell, scale, or stay independent.

The second founder must chase a unicorn outcome or fail trying.

How many paths do you still have open?

Over-capitalized founders face binary outcomes: massive exit or nothing.

Founders who raised conservatively can exit profitably at lower valuations, take dividends, or bootstrap to sustainability.

How close is your business to truth, not theater?

Do you have real customers paying real prices, or are you burning capital to acquire users who will churn when subsidies end?

The goal isn't to never raise capital. Capital, deployed strategically, can accelerate real opportunities. The goal is to stay in control long enough to choose the ending you want, not the one the market forces on you.

What Changes

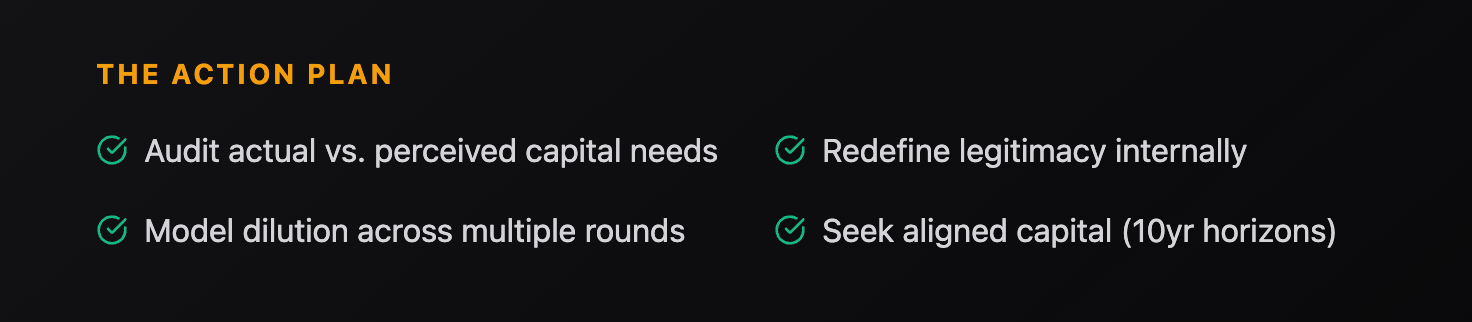

Founders need to audit actual capital needs versus perceived needs. Calculate true runway requirements for reaching profitability or the next major milestone, not just for reaching the next round.

Redefine legitimacy internally before seeking external validation. Company health should be measured by customer willingness to pay, unit economics, and product-market fit, not by capital raised.

Build a cap table strategy, not just a fundraising strategy. Model dilution across multiple rounds. Understand liquidation preferences and participating preferred terms. Know at what ownership percentage you lose practical control.

Seek capital from aligned sources. Funds with 10-year horizons, experience with profitable exits, and willingness to support alternative paths are worth more than funds optimizing for deployment speed.

Consider alternative funding structures. Revenue-based financing, venture debt, family offices, and strategic corporate capital can provide runway extension without equity dilution.

Build relationships with founders who've walked alternative paths. Profitable D2C brands, bootstrapped SaaS companies, and regional category leaders won't make headlines, but they provide the playbook the ecosystem refuses to write.

Recognize that you're not optimizing for a funding round. You're optimizing for an outcome. The best outcome is one where you retain enough ownership, control, and optionality to choose your own ending, not have it chosen for you by a preference stack you built one round at a time.

The venture trap persists because we keep walking into it, knowing the math but acting like the math doesn't matter. The first step out is recognizing that the ecosystem's definition of success and yours don't have to align.